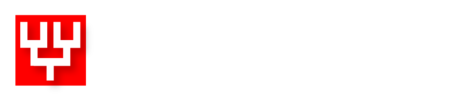

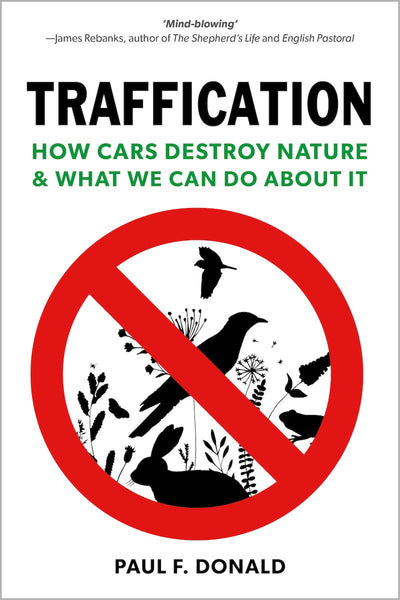

Paul Donald talks to us about Traffication and his bold new explanation for the drastic loss of wildlife from our countryside.

Firstly, could you tell us a little about your background and where your interest in the subject of Traffication began?

I’m a conservation scientist. For over thirty years I have worked in the research teams at the British Trust for Ornithology, the RSPB and now BirdLife International. I started out, like so many other conservation scientists of my generation, working on the impacts on wildlife of agricultural intensification but I have lots of research interests. I’m something of a jack of all trades when it comes to research, and never really specialised in anything. I’m glad, because I’ve been able to work on a huge range of subjects, from studies of Sociable Lapwings in the steppes of Kazakhstan and rare larks in Africa to research on sex ratios in vertebrates to investigations into the impacts of climate change in Ethiopia. This broad range of experience stood me in good stead when I took the plunge and decided to write Traffication, an idea that has been nagging away at me for many years. My parents are life-long pedestrians and have never driven, and even though I am a driver some of their unease about the impacts of car travel has clearly rubbed off. I just could not understand why, despite a torrent of recent scientific research showing road traffic to be a massive threat to biodiversity, in many different ways, the conservation movement seems to have a complete blind-spot for the subject. Then I realised that nobody has tried to pull all this evidence together, to make the case that driving might be one of the worst things we do to the planet, so I thought I’d better give it a go. Traffication is the result.

What was the biggest challenge you faced whilst writing the book?

The book covers a huge range of issues, because road traffic causes a massive range of environmental problems, and some of them inevitably fall outside my field of expertise, so I had to give myself a crash course on things the measurement of sound, the chemistry of air pollution and the physics of light. I had to read and digest literally hundreds of scientific papers and reports. But I learned a huge amount. It is no exaggeration to say that I see the world in a different way now.

You use the word ‘traffication’ as an umbrella term for the effects of road traffic; how did this originate?

Isn’t it strange that there is no word in the English language to summarise the growth in vehicle numbers over the last century, and the extent to which they have invaded our lives? It’s one of the most profound social changes of the last hundred years, yet we don’t have a word for it. I needed a word to describe the problem the book addresses, so I came up with traffication. It isn’t a very nice word but it’s the best I could do. I think the lack of such a word is part of the reason that conservationists and others do not regard the burgeoning of road traffic, and the extent to which it has spread across the country, as a threat – because if you don’t have a word for something, how can you even begin to talk about it?

Of the information that came to light during your research for the book, what surprised you the most?

Without doubt the impacts of traffic noise pollution, not only on wildlife but on our own health. Tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of people die from exposure to traffic noise in Europe each year. Noise causes stress, and long-term exposure to stress kills. It’s the same for wildlife. There’s now a huge body of scientific evidence to show that noise pollution may be the biggest impact of road traffic, far bigger even than roadkill. Noise drives down populations of birds and mammals for hundreds or thousands of metres either side of roads – and in the UK, with its dense road network, that’s pretty much everywhere.

What advice would you give someone looking to reduce the impact of their road activity?

Drive less and, even more important, slow down. Just about all the problems you cause by driving – to wildlife, to the environment and to human health – increase exponentially with speed. By dropping your speed by just 10 mph, you might be halving some of the damage you cause.

Are you optimistic about the future as regards road traffic and its impact on nature?

Yes, uncharacteristically so, for a number of reasons. We are understanding the problems better, we are developing technologies to minimise them and, most of all we are starting to move away from cars, in cities at least. For the first time in motoring history, the proportion of young people learning to drive is falling. Many organisations are now campaigning to lower car use, on the grounds of health, safety, aesthetics and so forth. Only the conservation organisations seem to be absent from the de-traffication party. My book is an attempt to invite them in.

Discover more about Traffication here